The powerful yet beneficial dragons of Eastern mythology form a complete contrast to the fire-breathing monsters of Western legends

In East Asia, dragon myths have a totally different origin from those that developed in the West, and they therefore cannot be seen as the same creatures. East Asian dragons are benevolent and are much more friendly and well-meaning than those in the West. In both Chinese and Japanese culture, dragons have similar representations and enjoy the same mythological status.

Water, rather than fire, was always the element associated with dragons in early civilisations.

Many people believed that the earth was surrounded by water with the sky forming a thin cover keeping water from flooding in, but giving sufficient water in the form of rain. The dragon was an ambiguous creature in that it was referred to as the monster who held back waters, which was a necessity for humans, while at the same time slaying the dragon meant disastrous floods and misery. This seems to point to a similarity between the ancient Sumerian idea of a dragon and the Chinese dragon or ‘lung’.

SPONSORED

The appearance of the first dragons in the West was recorded in Sumerian mythology in the form of battles between a god and a dragon named Kur. This god-dragon battle is a theme recurring in most Western cultures, and seems to have originated from the creation myths about the struggle between God and an aquatic monster. Not only was it the main theme of Sumerian dragon myths but it also recurred later in Semitic stories.

Dragon Origins

The English word ‘dragon’ comes originally from the Greek, drakon, which refers to a mythical monster resembling a huge lizard, usually with wings and claws, able to breathe flames. The original drakon was identified by the Greeks as part of the natural chaos that had to be overcome before cosmic order could be achieved.

In Greek mythology the dragon was the largest monster ever recorded. The drakon Typhon was so powerful that it frightened off the Olympian gods. It was finally conquered and slain by Zeus. A similar battle occurred between Apollo and Python. Greek dragons/serpents were ambiguous creatures, although Typhon was conceived of as more a primitive symbol of evil and destruction.

It was only in Semitic myths that the dragon/serpent became a creature of seductive knowledge as found in the Old Testament. The dragon became associated with the guarding of treasures – such as keeping Heracles’ apples of immortality from human access. Thus the slaying of the dragon (to gain access to these treasures) has been a mythological tradition in these cultures. This has been a fundamental difference between dragons in the West and those in the East, particularly the Chinese dragon or lung.

The Hebrew dragon tli is the closest to the Chinese idea of a lung. ‘For just as the world with all that is in it is ruled by the tli and the sphere, so is man ruled by the heart. The tli is in the world like a king on his throne.’ Just as the Chinese lung was always used to symbolise the Emperor, so the tli is almost as revered as the Chinese lung.

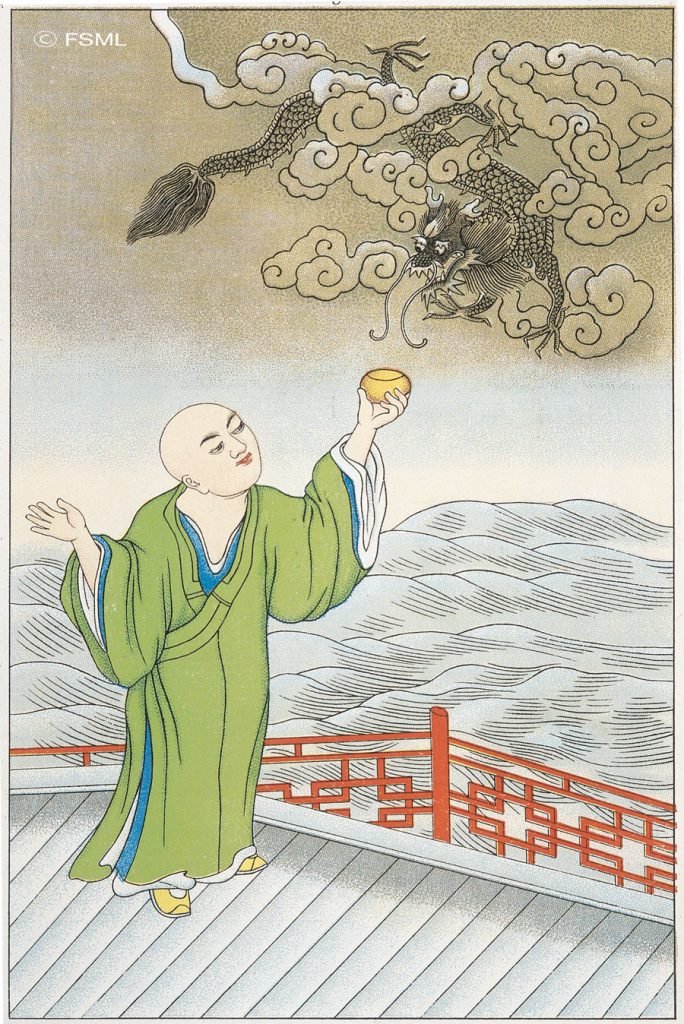

Chinese dragons or lung are the most sacred and ancient creatures in Chinese mythology. They symbolise not only good fortune but also grandeur and power. They are an emblem of wisdom and celestial dignity. Whereas dragons in the West breathe fire, Chinese dragons breathe clouds. In China they conferred Imperial legitimacy, as dragons were believed to attend the births of emperors and sages.

During the reign of Chin Shih Huang (late third century bce) and the subsequent Han dynasty (206bce-220ce), the dragon became closely linked with political power, to the extent that the Emperor was seen as the reincarnation of a dragon god. This tradition continued and was elaborated on until the Yuan dynasty (1271-1367) by which time Imperial dragons began to have five claws, and ordinary people were allowed only to depict their dragons as having three or four.

‘‘The slaying of the dragon… has been a fundamental difference between dragons in the West and those in the East”

Dragons Of Heaven And Earth

There are said to be four main kinds of Chinese dragon: the spiritual dragon (Shen lung) which is believed to be in charge of weather changes and is the most popular dragon in Chinese mythology; the Celestial dragon (T’ien lung) as seen in Lung Pao (the Dragon gown worn by the Emperor); the dragon of the Earth (Ti lung) which has power over waters; and the dragon of Hidden Treasure (Fu-ts’ang lung).

The lung has always been connected with the idea of nature in Chinese beliefs and with people’s relationship to nature. Many natural events were thought to be the result of dragons’ movements, such as dragons fighting in water causing floods. Water as a major association is particularly apparent in the Chinese idea of lung. Since water has great significance in an agricultural society such as that of China, so water-related natural forces were of paramount importance.

In terms of its connection with nature and natural phenomena, it was also believed that the dragon loves collecting pearls and chasing the moon, which is the largest pearl in the sky! When a dragon finally gets hold of the moon or the sun and swallows it, this creates an eclipse.

The pearl loved so much by the dragon is, as can be seen in many ancient art works, the emblem of the yin and yang life forces, like moon or sun, which form the dualism of nature, and which is the centre of feng shui beliefs. The dragon’s legendary spiritual and physical power is embodied in this yin/yang symbol.

This dragon-pearl connection can also be seen in the Hebrew tli dragon which is connected to the heavenly forces, ruling all the planets and the constellations. The main difference between this and the Chinese lung is that the Chinese dragon was never characterised as an evil serpent.

Dragon Veins And Ch’i

For the Chinese the lung symbolises a constant flow of energies and change, just as the yin and yang combination is a constant, ongoing exchange and merging of forces that form life itself. According to Taoist philosophy, the world is enveloped in dragon ch’i, which is part of the universe controlled by the 10 Celestial Stems and the 12 Terrestrial Branches. Ch’i is the life force and dragon ch’i is the beneficial life force. Thus ‘dragon veins’ (lung mai) control the flow of beneficial ch’i under the ground.

The Chinese in ancient times also linked the dragon with the East, a direction associated with new life, sunrise and Spring. A recent excavation of a Neolithic tomb discovered a stone dragon to the East side of the dead. To the West of the dead was a tiger, the dragon’s directional counterpart in ancient Chinese feng shui. This dragon-tiger symbolic association has remained the same to the present time in the everyday practice of feng shui.

For the Chinese, the dragon is synonymous with immortality. It has the power of transformation, hence the saying ‘fish leaping through the dragon’s gate’ (yu yue lung men). This phrase refers to successes in life that mark a turning point, which is why people used it in connection with men

who passed the very competitive civil service examinations in Imperial China. The same notion is still prevalent today.

“In the East a pearl-loving dragon is seen as embodying life forces”

The meaning of dragon widened over time. Sometimes modern-day Chinese sentimentally call themselves ‘descendants of the dragon’. In contemporary literature and folk music, ‘dragon’ is a word often used as a synonym for China. ‘Open your eyes wide, dragon’, ‘Wake up, dragon’ are phrases that have aroused nationalist fervour and encouraged nostalgia for the Motherland, recalling a time when a semi-colonial China was carved up by the Western powers.

Japanese dragons, though benevolent, seem more mysterious and awesome than the Chinese versions. They are a product of the mixture of borrowed spiritual and religious ideas, ie. Buddhism from India, by way of China. This mixture can be seen in the much more serpent-like shapes of Japanese dragons and their almost demon-like faces. Most of them are treated like sea gods, providing guidance for the fishing population, and were worshipped as such.

East V West

The mythology of dragons in East Asia reflects the generally presumed relationship between human beings and nature in Eastern thinking. Even for Confucius, who did not talk about ‘unknown natural forces’ or ‘spiritual beings’, there was no ambiguity: human beings are seen as part of all-encompassing nature.

Symbolically in the Christian West a dragon slayer – as illustrated by the legend of St George – was always seen as a hero acting on behalf of humanity and the death of a dragon a final triumph. In the East it was considered a rare, honourable, ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ experience to see a dragon with your own eyes. In the East a pearl-loving dragon is seen as embodying life forces, whereas a maiden-stealing Western dragon is seen as something that needs to be destoyed. This view of dragons was long reinforced by the early Church, which for many centuries was the centre of people’s lives and their most important ideological institution.

It is probably fair to say that in the West the history of dragons is one of struggle and repression, whereas in the East that history is one of coexistence and harmony.

SPONSORED